Geodesign

A project by: Fabio Gigone

With: Ludovico Centis, Marco Ferrari, Matteo Ghidoni, Michele Marchetti, Giovanni Piovene

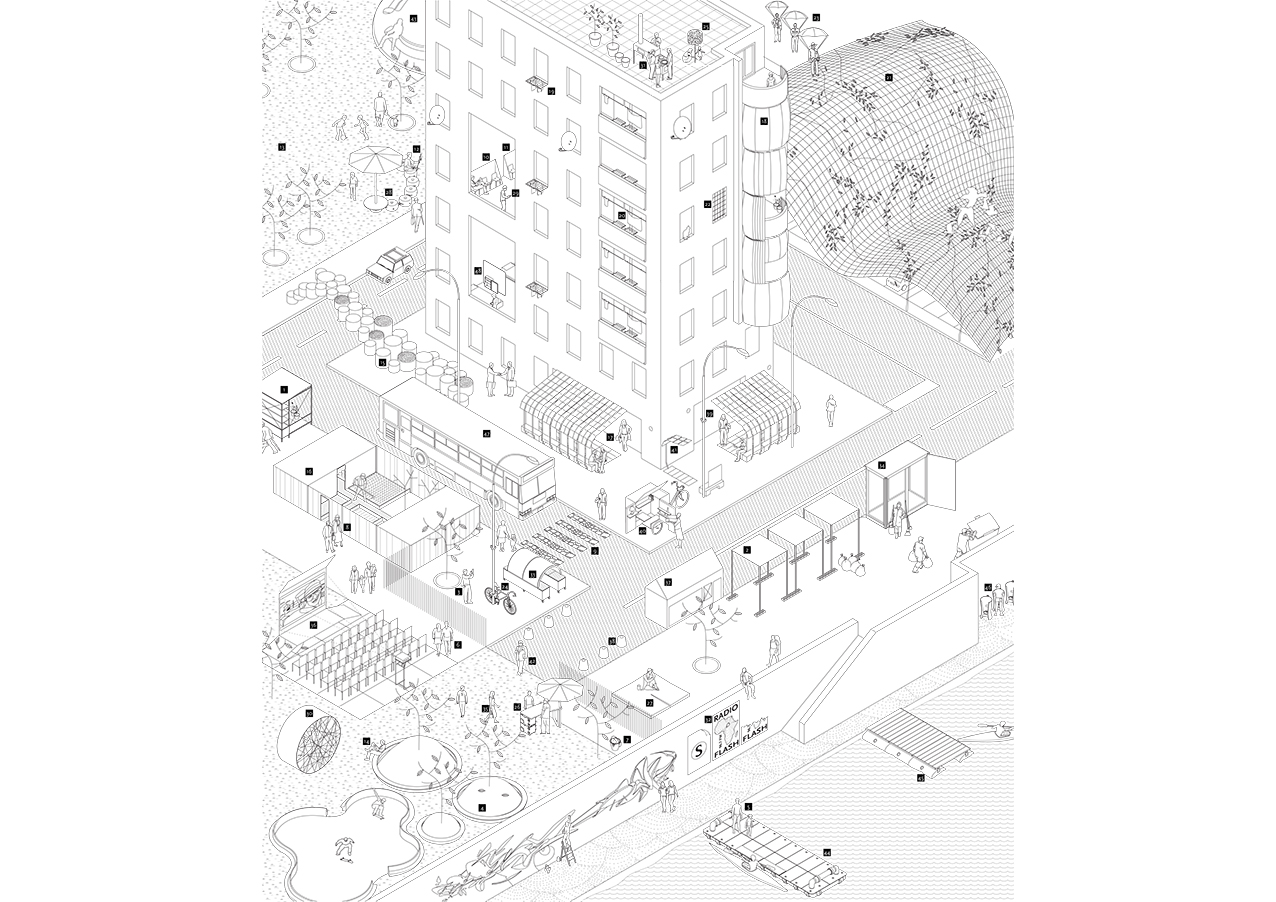

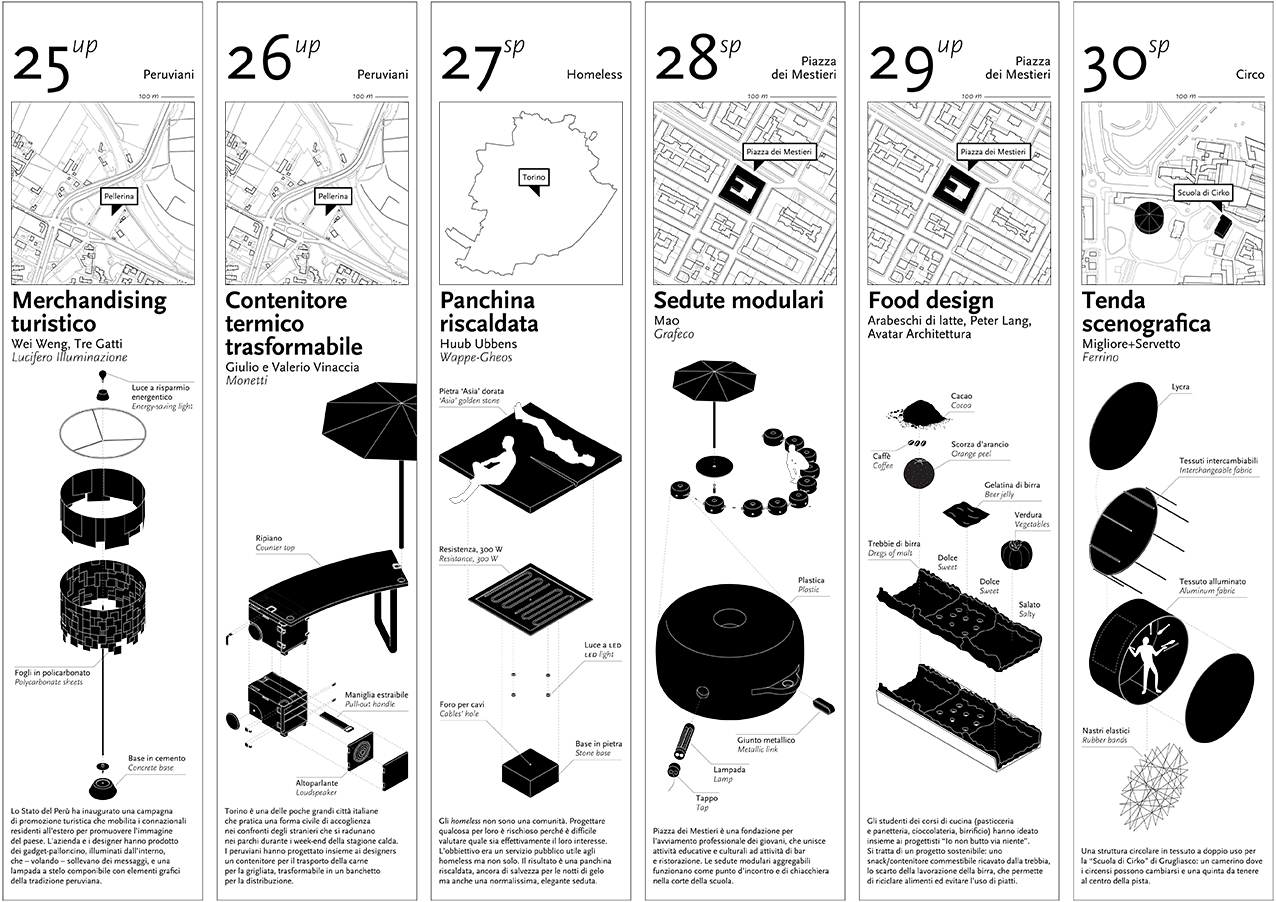

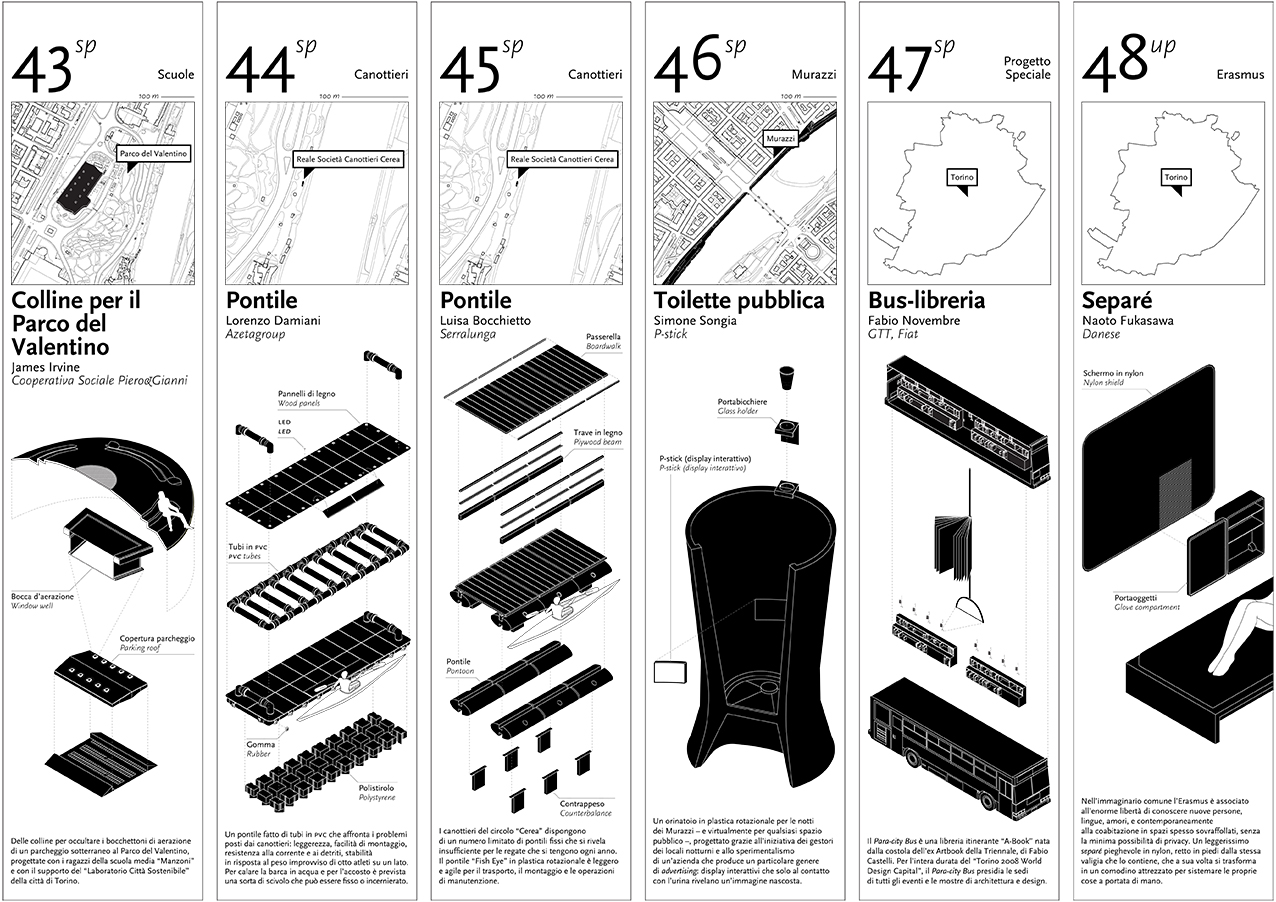

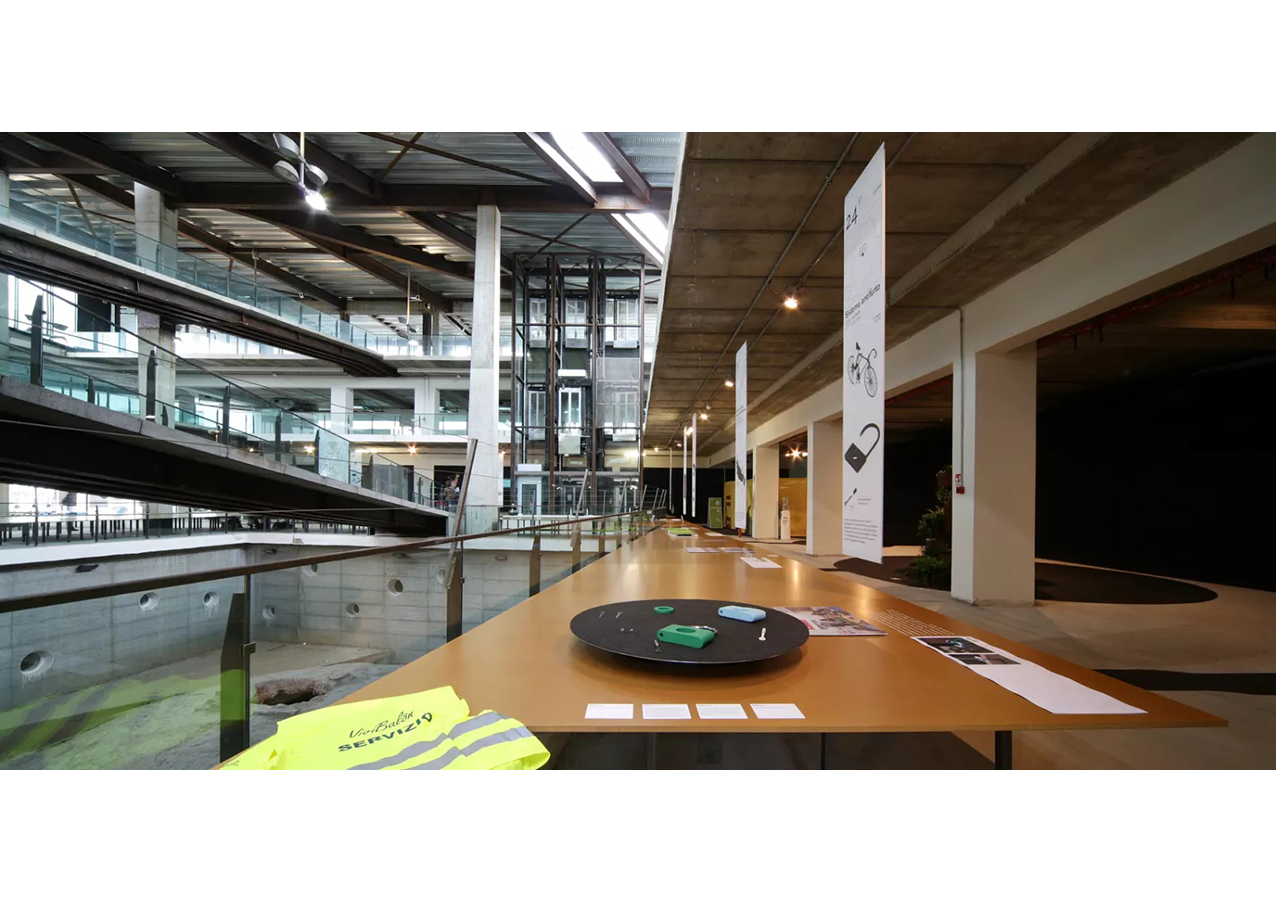

Geodesign is a project made in cooperation with local communities of Turin, international designers and design firms. It aims to the production of design objects, in a participative process that leads to the creation of a final device starting from the basic needs of a community. The results of these processes have been shown inside PalaFuksas (Turin) from May 24th, 2008 to July 06th, 2008.

Design as accelerator, by Lucia Tozzi

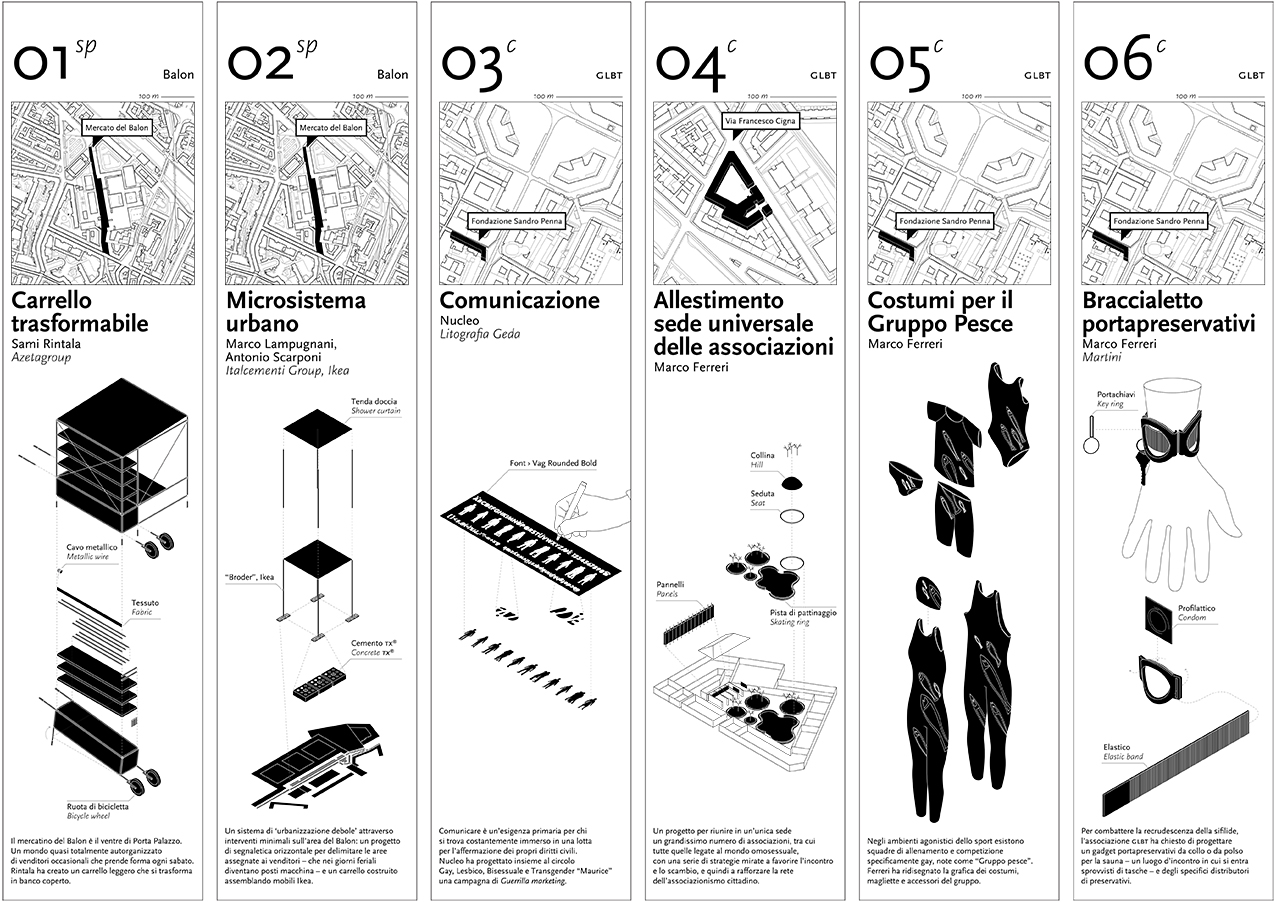

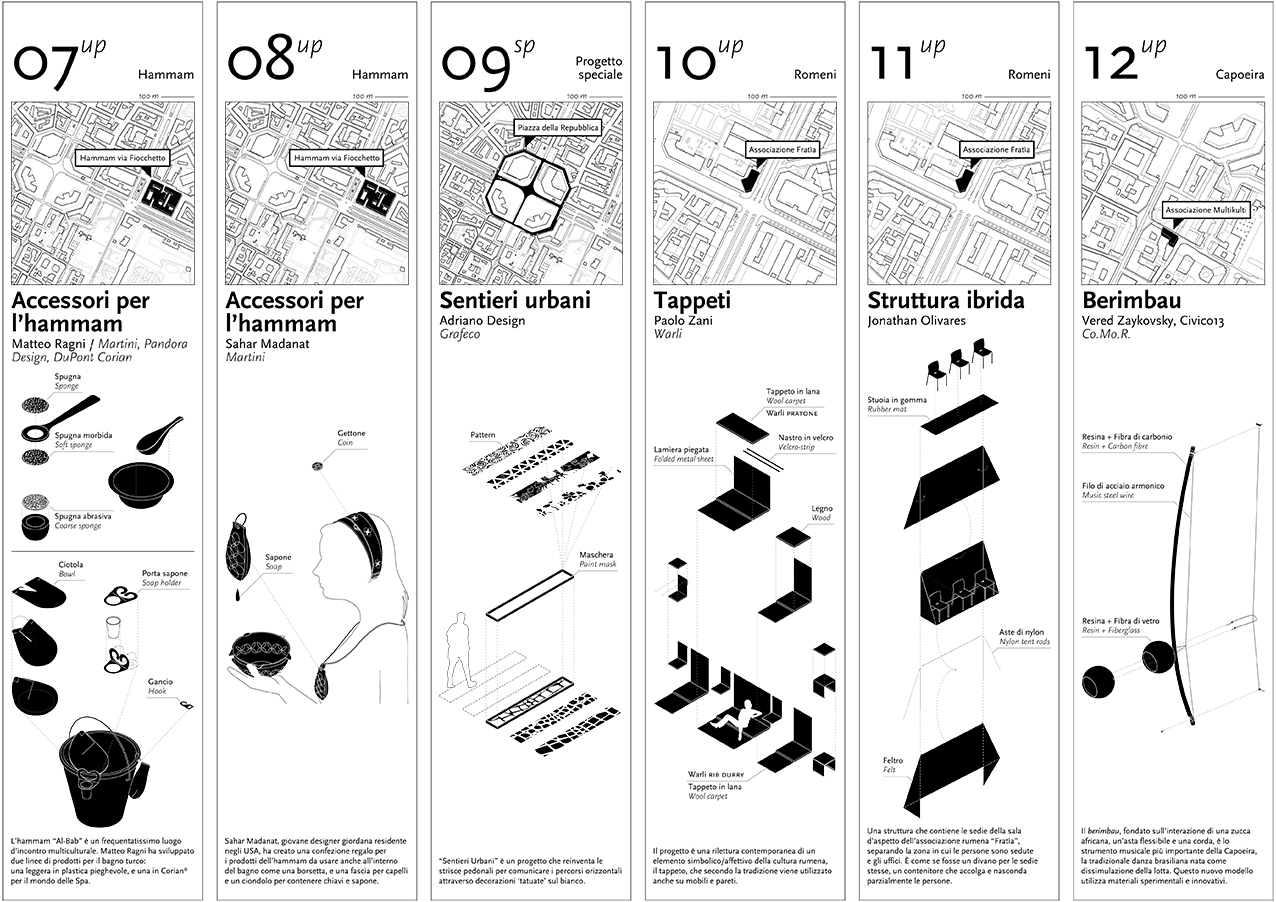

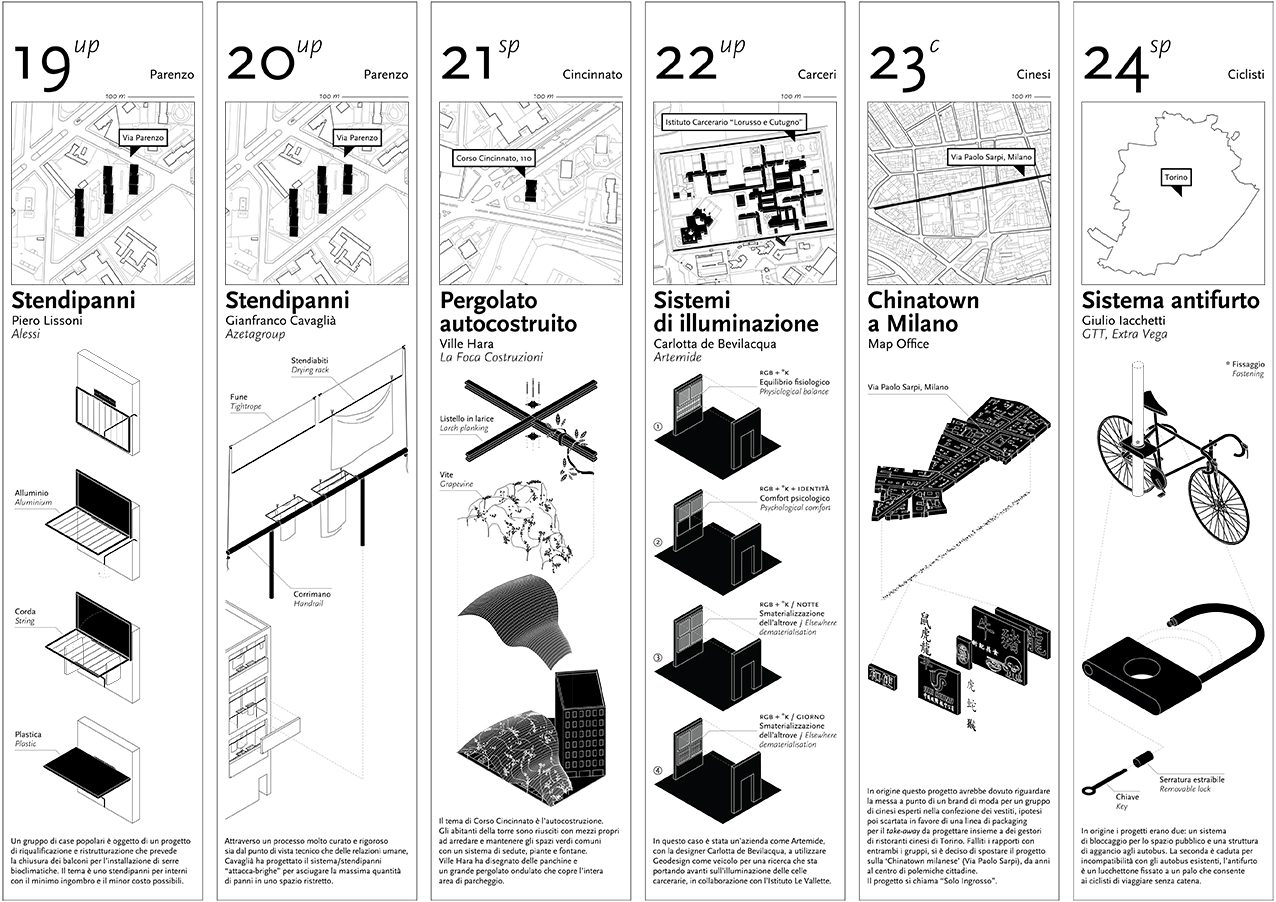

In any discussion about design and democracy, it seems necessary to think of solutions to basic problems or very basic needs: a filter for the purification of water in an African village, a water-free toilet in the favelas of Caracas, or at the very least a virtual wall to project onto traffic lights to try to prevent the ritual sacrifice of pedestrians in our cities. This rule didn’t apply to Geodesign. During this process, which lasted for more than a year, over forty groups of people in Turin were found, questioned and mobilised, in order to create a link between their desires and skills and those of designers and companies. With Geodesign, it was immediately clear that no one wanted to design those kinds of objects. Foreigners weren’t interested in designing tools to live more comfortably in their homes or in order to optimize their work. They were interested in their free time (the barbecue in the park for the Peruvians, for example) and in promoting their own cultures (a magazine for Albanians and a radio for Africans). The bocce ball players weren’t interested in outdoor furniture, even though those they had were a little wobbly. They wanted a system for coloring the metal balls they used in the game. These and other requests are only seemingly frivolous. You would have to be insane to deny the strategic importance of media access and intercultural dialogue in the world today and in particular in contemporary Italy. It is an obvious point that immigrants have problems in finding public spaces where they can meet on weekends. Colouring the bocce balls signifies participation in the Olympics. The players are not pensioners who need more comfortable chairs in order to while away their time. They are competitors, people who realise that cultivating their passions and ambition is the best way to take care of their own well-being. Geodesign was an opportunity to demonstrate something to an inattentive market and society (which is too ideologically bound to a series of stereotypes and to the religion of marketing, where needs are merely induced) that there are a number of non-standard needs, which emerge from schools, prisons, paediatric hospitals, working-class housing, and outdoor markets and through discussions with groups of athletes, homeless people, cultural organisations and restaurant managers. The project’s political power goes beyond these needs – it locates them in a network. Without question, the energy and diplomatic skill that went into linking a designer and one or more companies with each of these problems produced some unexpected results: new human and commercial relationships, new curiosities, as well as new, and useful, conflicts at all levels.The interesting thing is that Geodesign developed a clear definition of how to act in terms of democratic design. Design in any of its forms, including those linked to technology and communication, will never be the primary force behind social and individual wellbeing. People know that it is better to work hard or use politics to improve their situation and surroundings. Only by linking up with the tools which are needed to change things (above all well-invested cash and legal reform) design can properly utilise its power to offer quick, intelligent and rational – if temporary – solutions. Design’s democratic power needs to be understood in terms of its limitations, which are intellectually significant and less presumptuous. It is a matter of going beyond the old saying, “necessity is the mother of invention”, with its charming Robinson Crusoe-style lists, a design of needs, the creativity of favelas or post-Soviet society. Design is an accelerator, an active form of manipulating reality, and a way of operating that can upset basic schema. Without disturbing feasible Utopias and détournements, it allows for action through logical leaps, which are unthinkable in other fields, as in psychoanalytical therapy. But lets get back to Geodesign, where a number of very serious issues were approached in a truly original way. For example, the GLBT (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender) association wanted to help condom use to fight the return of syphilis, concentrating on one of the typical spots for homosexual encounters, the sauna. Only design offers the chance to pose this question in terms that are not moralistic: how can we make it easier to bring condoms to a place where you go without clothes and bags, and design finds the solution in a gadget to wear around the neck or wrist. Or, for example, there is the difficult issue of contested public space. The residents of Piazza Madama Cristina, wanted to defend themselves from constant illegal parking. Typical solutions would be bollards, which do not work because there is a market in the morning, or a traffic policeman, who is apparently not available, or automatic retracting bollards, which are expensive, or a new urban planning set-up for the square, but that takes time. Jasper Morrison designed fixed rubber seats that disappear under the market stands in the morning and keep cars away in the afternoon. Not all of these experiences were successful. Some communities resisted change and some designers could not move beyond their concepts towards practical solutions; the companies often placed narrow limits on the work and the organization was not always adequate. These are the most interesting cases.